Thalassemia often hides in silence. Most carriers have no symptoms at all. This makes early detection difficult. Parents might not realize they both carry the gene. When two carriers have a child, the risk increases. Some children inherit a severe form. Others carry the trait unknowingly. Many people carry the gene without knowing it. It spreads quietly through generations.

Blood transfusions are frequent, but they aren’t enough

For many with thalassemia major, transfusions are essential. They happen monthly, sometimes more often. These keep hemoglobin levels stable. But they aren’t a cure. Repeated transfusions cause iron buildup. That iron damages the heart, liver, and other organs. Medication is needed to remove excess iron. Blood transfusions are frequent, but they aren’t enough.

The burden falls hardest on low-income countries

Access to treatment isn’t equal. In wealthier countries, regular care is possible. In poorer regions, supplies are inconsistent. Blood may be unsafe. Chelation drugs might be unavailable. Doctors may lack proper training. The burden falls hardest on low-income countries. Children die young, even though treatments exist. Geography often decides survival.

Families become full-time caregivers with little support

Thalassemia affects daily life, not just hospital visits. Parents adjust their work schedules. Siblings adapt to routines. School attendance becomes irregular. Travel plans revolve around hospital dates. Families become full-time caregivers with little support. Emotional fatigue builds over time. It’s a long journey with few breaks.

Iron builds up silently and damages vital organs

Iron overload is the hidden threat. It comes from the very transfusions that keep patients alive. Without chelation therapy, iron accumulates. It settles in the liver, heart, and glands. Organs begin to fail without clear warning signs. Iron builds up silently and damages vital organs. The damage is preventable, but only with regular treatment.

Screening before marriage prevents many cases

Prevention works. Blood tests before marriage help identify carriers. Many countries promote this. Some require it by law. If both partners are carriers, they can make informed choices. They might use IVF. Or decide not to risk inheritance. Screening before marriage prevents many cases. It’s cost-effective and simple—but still underused.

Education levels shape awareness of the disease

In many regions, people haven’t heard of thalassemia. They confuse it with anemia. They don’t realize it’s genetic. Schools don’t teach it. Doctors don’t always explain it clearly. Education levels shape awareness of the disease. Without information, prevention stalls. Misunderstandings lead to more affected births.

Research funding lags behind other chronic illnesses

Thalassemia isn’t rare. But it receives little attention. Big breakthroughs are few. Clinical trials are slow. Funding flows toward more visible conditions. Pharmaceutical companies hesitate to invest. Research funding lags behind other chronic illnesses. Yet the global impact remains massive. The silence around it continues.

Bone marrow transplants offer hope, but not access

A cure exists: bone marrow transplant. But it’s expensive. It requires perfect matching. Most patients can’t find donors. Transplants are risky, especially in older children. Success rates depend on age and health. Bone marrow transplants offer hope, but not access. Most families can’t even consider it.

Children often grow slower than their peers

Growth delays are common. Thalassemia affects hormone production. It stunts height and delays puberty. Children notice the difference early. They feel out of place. Schoolmates ask questions. Self-esteem takes a hit. Children often grow slower than their peers. Without hormonal support, development stays behind.

Women with thalassemia face pregnancy risks

Fertility is possible but complicated. Iron overload affects reproductive organs. Heart function becomes a concern. Some medications must stop during pregnancy. Close monitoring is essential. Risk of miscarriage is higher. Women with thalassemia face pregnancy risks. Many still choose motherhood—with careful planning and care.

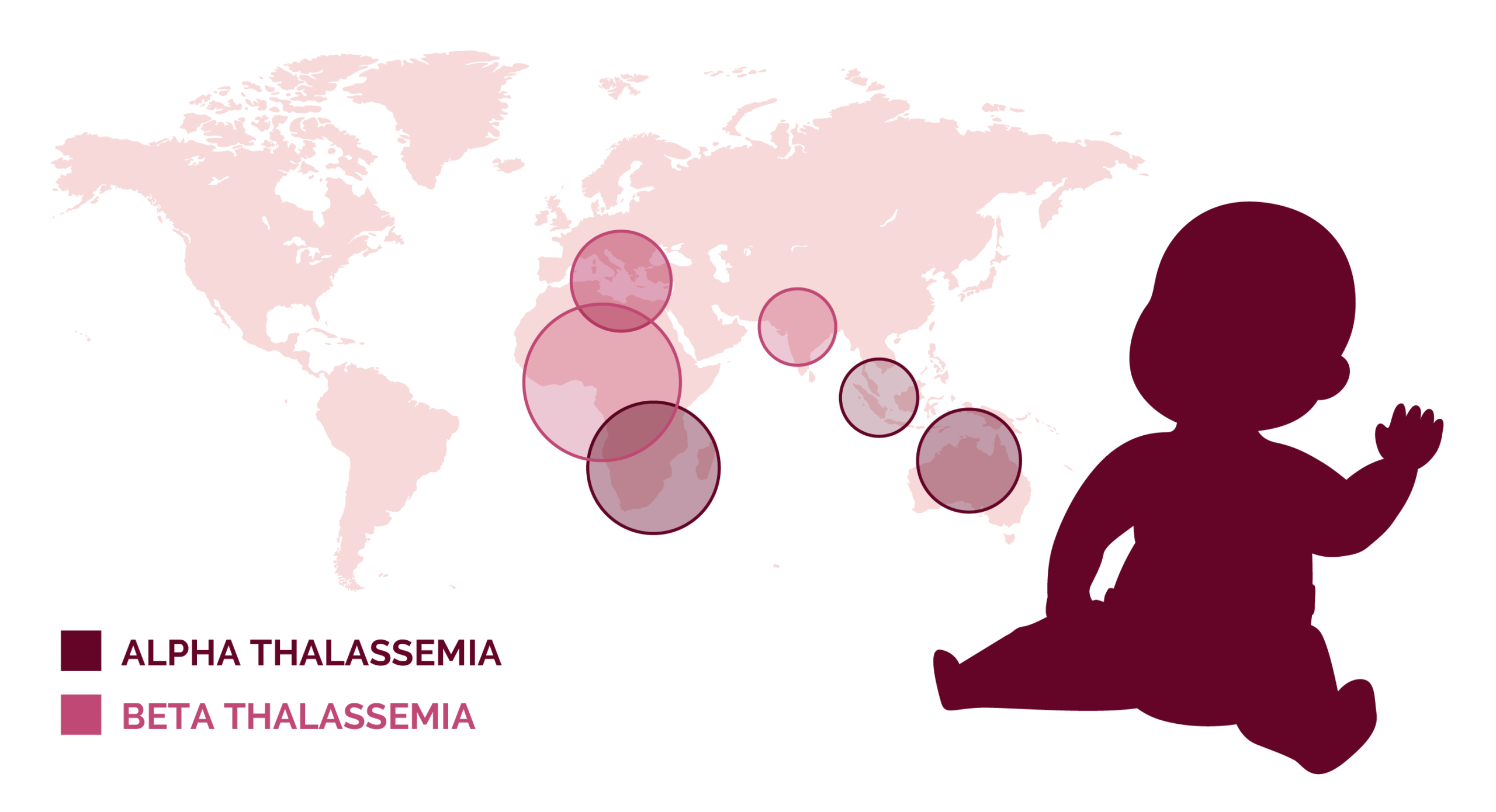

Thalassemia traits offer protection against malaria

There’s a reason the gene survived. In areas with malaria, thalassemia provided an advantage. Carriers resisted the disease better. Evolution favored the trait. That’s why it’s common in the Mediterranean, South Asia, and Africa. Thalassemia traits offer protection against malaria. But the price is a lifelong blood disorder.

Mental health care is often overlooked in treatment

Living with thalassemia is draining. The hospital becomes a second home. Social life suffers. Teenagers feel different. Adults burn out. Anxiety and depression are common. But mental health services are rare in hematology clinics. Mental health care is often overlooked in treatment. Emotional pain compounds the physical struggle.

Global migration spreads the condition beyond its origins

Thalassemia isn’t confined by borders. Migration carries it globally. It’s now seen in places once unfamiliar with it. Healthcare systems must adapt. Screening protocols lag behind. Misdiagnosis is common. Global migration spreads the condition beyond its origins. Cultural sensitivity and updated training are essential.

Blood supply must be consistent, safe, and community-driven

No transfusion happens without donors. Safe blood depends on public participation. Yet myths and fear reduce donation rates. In rural areas, storage is poor. Transportation delays waste valuable resources. Blood supply must be consistent, safe, and community-driven. Every unit counts. Especially in emergencies.

Advocacy efforts need more visibility and coordination

Few speak loudly for thalassemia. Campaigns remain small. Language barriers limit reach. Patients advocate alone. Coordination is weak between countries. Global events are rare. Advocacy efforts need more visibility and coordination. More voices could shift funding, awareness, and policy.

Patients become medical experts by necessity

Many patients learn medical terms early. They understand hemoglobin levels, chelation schedules, drug side effects. Appointments are dialogues, not lectures. They question doctors. They manage their own records. Patients become medical experts by necessity. Their insights deserve respect in research and treatment design.

Public policy must adapt to long-term care realities

Thalassemia doesn’t end at age eighteen. Adult patients need ongoing care. Many lose insurance. They fall through systems built for children. Job discrimination remains. Marriage prospects suffer. Public policy must adapt to long-term care realities. Survivorship is growing. Systems must evolve with it.